Liu Xiao Bo – Ai Weiwei

On July 13 2017, activist, writer and Nobel Peace laureate Liu Xiaobo passed away in government custody.

He advocated for non-violent action, participated in the Tiananmen Square pro-democracy protests, and helped to draft and gather support for Charter 08, a call for peaceful political reform and an end to one-party rule. He spent almost a quarter of his life behind bars in China for advocating human rights and democracy.

Once the news of his death became public, one related phenomenon started to be reported. References to Liu Xiaobo, his work, and his passing were being censored on social media in China more harshly than ever before.

Social media platforms in China regularly censor content related to Liu Xiaobo and his legacy. But since his death, even just typing his name in a message or trying to share an image of him in a one-to-one chat has become enough to get the message blocked.

In response to this violation of freedom of expression, a growing number of internet censorship researchers, journalists, and human rights activists has been publishing articles and studies attempting to document the nature and extent of the censorship measures adopted to silence communications about the dissident’s death.

This post presents a collection of reports and analysis published on the topic to date. They are organized in chronological order to best follow through subsequent updates as they were made public.

Selected readings

This reading list aims to serve as a resource to gather information about the internet censorship measures employed following Liu Xiaobo’s passing, to the extend of what has been reported so far.

The selection of the articles was guided by the intention to represent the perspectives of as many actors involved as possible. Not much has been disclosed by government and corporations of course. However, internet users, independent reporters, and technology researchers have been documenting and sharing their findings and analysis online, and this is the wealth of knowledge that this list wants to call attention to.

How Chinese internet users got round censors to mourn Liu Xiaobo – Eva Li, South China Morning Post

“Censors appear to have stepped up their surveillance and cast a wider net to catch posts with indirect references Liu as news of his death spread.

The most recent 200 Weibo posts deleted on Weibo were all related to Liu’s death on Friday morning, according to Weiboscope, a University of Hong Kong project that tracks censorship on the social media platform.

None of the deleted tweets contained Liu’s name, with many referring to the activist simply as “him”.

Nearly a 10th of the censored posts after the announcement of Liu’s death on Thursday night contained the Chinese words for “rain” and “storm”.

Some of the messages trying to circumvent censorship by adding text inside pictures were also blocked.”

China’s censors are making sure the country doesn’t remember human rights activist Liu Xiaobo – Echo Huang, Quartz

“Since last night, Weibo has also indicated that creating a post with a candle emoji or “RIP”—even if Liu isn’t mentioned—is a “violation of laws and regulations.” […]

Other keywords translating to “compassion release,” “late-stage liver cancer,” “Liaoning prison,” and “an empty chair” are among the only still available (so far) for news about Liu. “Empty chair” refers to Liu’s absence at the 2010 Nobel Prize award ceremony.”

Chinese citizens evade internet censors to remember Liu Xiaobo – Javier C. Hernández, The New York Times

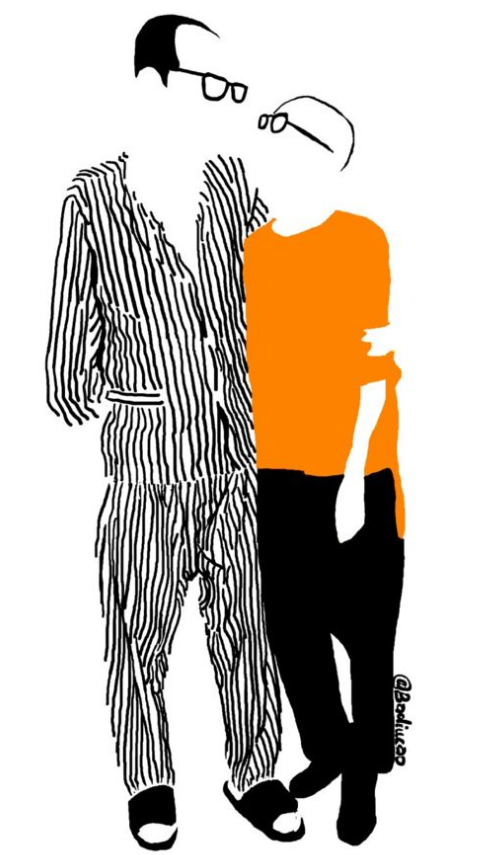

The patient of China, an artwork by political artist Badiucao, portraying Liu Xiaobo and his wife, Liu Xia.

Despite censorship, netizens remember Liu Xiaobo – Josh Rudolph, China Digital Times

“Among the terms blocked from Weibo search results:

- I have no enemies (我没有敌人): the title of the powerful statement read by Liu as he was sentenced to 11 years in prison in 2010.

- Aesthetics and Human Freedom (审美与人的自由): the title of Liu’s 1988 PhD dissertation, later published as his second book.

- Mister Liu (刘先生)

- xiao bo

- Xiaobo (晓波, 小波): alternative spellings of Liu’s given name.

- LXB

- Aspergillus flavus (黄曲霉素): A pathogenic fungus known to cause liver cancer in mammals. There has been speculation that Liu was served spoiled food during his imprisonment.

- RIP.

And among the terms forbidden from being posted on Weibo:

- Candle (蜡烛): At Mashable, Yi Shu Ng reported that even the candle emoji was disabled on Weibo.

- Liu Xiaobo (刘晓波)

- liu xiao bo

- I have no enemies (我没有敌人)

- Fearless (无所畏惧)

- RIP, R.I.P. [Chinese]”

Chinese Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo’s death sparked an outpouring of grief online. Then came the censors – Jonathan Kaiman, with contribution of special correspondent Ralph Jennings in Taipei, Taiwan, and researcher Gaochao Zhang in the Los Angeles Times’ Beijing bureau.

“ […..] on Friday, China’s social media sites were filled with expressions of solidarity and grief, suggesting that Liu’s case — and his ideals — may be more influential in China than many outsiders believe. These expressions were often cryptic and muted — snatches of poetry, allegorical quotes — but still, the censors responded in force. […]

“I think this kind of pokes a hole in the narrative that he’s not well known in China,” said William Nee, a Hong Kong-based researcher at Amnesty International. “I don’t know if I’d characterize this as a paradigm shift. But it might be that some of the seeds he’d started to plant — or, the ideas in Charter 08 — have started to bear fruit among the rights defense community, and they’re becoming more well known and are spreading among parts of the general public”.”

China censors the candle emoji right after Liu Xiaobo’s death was announced – Yi Shu Ng, Mashable

“In the wake of his death, China’s government-influenced social media platforms have banned searches for his name, “Nobel,” the word “candle,” as well as “I have no enemies” — an essay Liu had prepared for his trial in 2009, that he wasn’t allowed to read.

Searches for these terms returned Weibo’s canned censorship message: “According to relevant laws and policies, the results you searched for cannot be displayed.”

“Our attempts to post a candle emoji also resulted in an error message.

Both Weiboscope and Free Weibo, which log deleted posts on Weibo, reported multiple posts with the candle emoji deleted […] Posts that simply had the crying emoji were also censored.”

Remembering Liu Xiaobo. Analyzing censorship of the death of Liu Xiaobo on WeChat and Weibo – Masashi Crete-Nishihata, Jeffrey Knockel, Blake Miller, Jason Q. Ng, Lotus Ruan, Lokman Tsui, and Ruohan Xiong, The Citizen Lab

“The scope of censorship of keywords and images on WeChat related to Liu Xiaobo expanded greatly after his death. Our analysis of WeChat keyword-based censorship shows that after his death messages containing his name in English and in both simplified and traditional Chinese are blocked. His death is also the first time we see image filtering in one-to-one chat, in addition to image filtering in group chats and WeChat moments.

Sina Weibo maintains a ban on searches for Liu Xiaobo’s name in English and Chinese (both simplified and traditional). However, since his passing, his given name (Xiaobo) alone is enough to trigger censorship, showing increased censorship on the platform and a recognition that his passing is a particularly sensitive event.

Based on an initial analysis of Weibo’s suggested search keywords, we surmise that there continues to be genuine user interest in producing and finding Liu-related content using alternative keywords.”

A world without Liu Xiaobo – Ronald Deibert, Director, The Citizen Lab, Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto

“Freedom of speech is the antithesis to one-party rule. Dictators throughout history have forced embarrassing truths into the shadows, typically by imprisoning those who speak it, and have scrubbed dissidents from history books, photographs, and other mass media.

The social media censorship we document in our latest report is but the latest manifestation of this authoritarian tendency, and underscores why careful evidence-based research is so essential to the progress of human rights.”

CyberChina (170709-170714) & some thoughts on Liu Xiaobo’s passing – Lotus Ruan

“Liu’s life and death also serves as a reminder of a conundrum individuals in China and Chinese leaders are facing: to what extent free thoughts are allowed? What is the line between innovative ideas and dissident voices that are “subversive”, “harmful to society” or “endangering national security”? Thanks to the government’s grand plans and almost unlimited resources on “Internet Plus”, artificial intelligence, etc, China is catching up, if not exceeding, Western countries in new technologies. New technologies are usually disruptive and require unconventional thinking that may break current social norms or even political orders.”

Censorship after death: Chinese netizens quietly mourn Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo – Oiwan Lam, Advox

“At present, Hong Kong may be the only city in China where citizens can publicly mourn the loss of Liu Xiaobo […]. On July 15, hundreds attended a candlelight vigil in Hong Kong and also demanded that authorities end house arrest for his wife.”

Pictures from the vigil in memory of Liu Xiaobo in Hong Kong – Venus Wu

Liu Xiaobo’s death pushes China’s censors into overdrive – Amy Qin, The New York Times

“The aggressive attempt at censorship is just the latest indication of the strong grip that the Chinese government maintains on local internet companies. In addition to automatically filtering certain keywords and images, internet companies like Baidu, Sina and Tencent also employ human censors who retroactively comb through posts and delete what they deem as sensitive content, often based on government directives.

Failure to block such content can result in fines for companies or worse, revocation of their operational licenses. Censors have been on especially high alert this year in light of the Communist Party’s 19th National Party Congress in the fall.”

WhatsApp falls victim to Chinese internet censorship in wake of Liu Xiaobo’s death – Ding Wenqi and Qiao Long for Radio Free Asia’s Mandarin Service, and Wong Lok-to for the Cantonese Service. Translated and edited by Luisetta Mudie

“Anti-censorship website GreatFire.org reported on Tuesday that the app was partly inaccessible from within the complex system of blocks, filters, and human censorship known as the Great Firewall.

WhatsApp, which is owned by Facebook and offers end-to-end encryption, isn’t as popular as its homegrown counterpart WeChat among China’s 731 million internet users, but has until now been more resistant to government censorship.

Social media users reported that their attempts to post banned photographs of Liu […] had failed on WhatsApp since noon local time. […]

The user said they had previously used WhatsApp to circumvent government censorship along with a group of more than 100 friends […].”

The Chinese language as a weapon: How China’s netizens fight censorship – Jeanette Si, Internet Monitor, Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University

“Since July 13, Weibo has blocked all mentions of the name “Liu Xiaobo,” the phrase “R.I.P.,” and even the candle emoticon. Searches for his name on many other sites would turn up empty. But at the same time, seemingly at random, came an influx of posts mentioning a certain “Wang Xiaobo” and another “Teacher Liu” — which were both, of course, cryptic nicknames for the late Nobel laureate. […]

It may seem like a convoluted system of doublespeak to some, but for Chinese netizens, this is the norm — and always has been. Much of Chinese Internet lingo involves codewords, and the corpus of codewords is constantly changing to accommodate new topics and avoid smarter, stricter censors. It has reached the point where a simple understanding of Chinese vocabulary, syntax, and grammar is no longer enough to fully understand Chinese Internet discourse. On today’s Chinese Internet, fully comprehending the language requires a thorough knowledge of current events, a deep respect for historical implications, an agile mastery of cultural conventions, and more often than not, a healthy appreciation of topical humor.”