On the upgrades of centuries-old systems of oppression and present-day tools to fight back

Yemeni women during a rally commemorating the fifth anniversary of the 2011 Arab Spring uprising. Taez, February 2016. AFP / Ahmad Al-Basha.

Globally, law enforcement agencies are adopting increasingly sophisticated surveillance technologies to employ predictive policing and monitor already overpoliced communities and demographics. Prevalent grounds for discriminatory conduct are race, class, citizenship, religion, gender identity, sexual orientation.

We hear from the news about phone interceptions, seized devices, hacked accounts. But most often, the civil society is provided with small to no information about how far these monitoring activities go.

How is technology employed to control targeted groups? And how can technology support who’s controlled to reclaim and protect their rights?

This article will examine how technology can serve very different purposes: from enforcing unequal monitoring protocols, to fighting abusive policing and shifting the balance of power.

It is written for:

- Activists, protesters, and members of discriminately monitored communities willing to know more about how technology can be employed to track them, and how secure tools can equip them to respond and resist to the abuse of power;

- Creators and supporters of technology projects eager to reflect on the demand for secure tools of resistance, and the need of systems and resources to support the development of tools informed, formulated, built by those who are experiencing the consequences of abusive policing first-hand.

More on the framework of this article

Technological innovation intertwines with how law enforcement agencies monitor their constituencies. Two core aspects of this dynamic will be examined in this piece: technology for surveillance, and technology for resistance.

Some of the most common types of surveillance technologies adopted by law enforcement agencies will be mentioned, not to focus on the details of their sophistication, but to underline how they help perpetrating centuries of inequality and abuse on targeted groups.

In response to those, this article will also feature examples of technology for resistance. These are tools developed to enable everyone to use information and communications technology within their right to privacy, and without being subjected to discriminatory monitoring and policing.

Wishing to examine the subject matter with an international perspective, while also having common ground to discuss it across geographical borders, this piece will focus on democratic societies.

With the aim to concentrate the attention on the most affordable and accessible technological solutions available to those who are the target of discriminatory monitoring, the analysis will center on smartphones and their communications and video documentation features.

A note on this choice: by 2020, 6.1 billion people are expected to be smartphone users, accounting for 70 percent of the world’s population; however, it’s important to remember that this type of devices require financial costs that many individuals in need might not be able to afford, and that the global availability of mobile technology, while rapidly on the rise, is still on a growing path.

[Warning: graphic content] Truth and Power – About The Issue: Activist Surveillance (#BlackLivesMatter). With Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, DeRay McKesson. Produced by Brian Knappenberger. Pivot.

Claims and loopholes

Before starting to review technological features, here is a note on political claims and policy loopholes that very often frame the scenarios we’ll look into.

To answer for their actions when it comes to the adoption of surveillance technologies, law enforcement bodies often claim to act in the name of national security. And this position shouldn’t go overlooked.

Constituencies worldwide are debating about the opportunities and risks presented by the adoption of surveillance technologies for law enforcement purposes. Framing such discussion in national security terms gives law enforcement agencies the chance to play on the angst of their constituencies, and potentially take advantage of it to justify the exacerbation of their practices.

Also, it is critical to observe that national security is not a neutral concept: it is inherently classed and raced, controlled by capital and power (and for anyone interested in exploring this notion further, these conversations from RightsCon and Georgetown Law’s The Color of Surveillance conference are an excellent primer).

It is in this context that blurred lines and loopholes can make room for practices far from democratic. What should be a statutory effort to preserve collective security can turn into abusive exercise of power. And the adoption of surveillance technologies can turn into discriminatory policing of communities, movements, and entire demographics.

Mobile phone communications

Mobile phone monitoring technologies capture information transmitted over mobile networks, and can take place with or without the cooperation of the network operator.

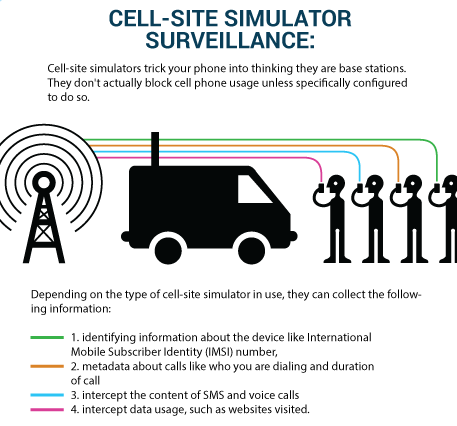

An example of this type of technology are cell-site simulators, also commonly known as IMSI catchers or Stingrays. IMSI stands for International Mobile Subscriber Identity, and it’s an identifying number that is unique to each cell phone.

As explained by the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Street Level Surveillance Project:

“Cell-site simulators […] are devices that masquerade as a legitimate cell phone tower, tricking phones nearby into connecting to the device in order to log the IMSI numbers of mobile phones in the area or capture the content of communications.”

As reported by Privacy International, “in some cases, the most sophisticated forms of IMSI catchers have the capability to intercept calls and even send messages to each registered phone.”

Cell-site simulator surveillance. From the Street Level Surveillance project website, Electronic Frontier Foundation.

Cell-site simulator surveillance. From the Street Level Surveillance project website, Electronic Frontier Foundation.

Of course this type of technology can greatly help law enforcement bodies to monitor individuals and groups suspected of severe crimes. But it has been repeatedly reported that cell-site simulators have also been used to monitor citizens who are not even suspected of a crime, and control the communications of movement organizers. Lawyers and civil rights organizations worldwide reclaim transparency and accountability when it comes to the adoption of cell-site simulators, but their use is still largely covered by secrecy.

Some examples of cases in which the adoption of cell-site simulators has been challenged as abusive and violating the right to privacy:

- In a report conducted by Outlook India in 2010, senior intelligence officials confirmed that cell phones of ordinary citizens were tapped without written authorisation from the Union home secretary, as mandated by law. Communications data were captured by operations vehicles carrying surveillance systems.

- In 2014 the Philippine government Department of National Defense acquired equipment with the capability to hone in on and intercept calls and text messages sent within a 500-metre radius of the device. The revelation prompted concerns by opposition groups that the government would use the technology to spy on them.

- In the United States, law enforcement agencies have been reported to use cell-site simulators to secretly track protesters as well as people who aren’t even suspects in a crime, raising privacy and constitutional concerns.

- Recently, it emerged that IMSI catchers have reportedly been deployed by the South African police. The Regulation of Interception of Communications and Provision of Communication-related information Act (RICA) does not regulate this type of technology. As reported by Privacy International, “it is not clear if the police applies for interception direction under RICA before deploying it”.

Phone Hackers: Britain’s Secret Surveillance. With Richard Tynan (Privacy International), David Davis. Produced by Ben Bryant, Vice News.

How can citizens prevent having their data captured by cell-site simulators?

As outlined by the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Street Level Surveillance Project:

“As of now, we know of no way to avoid having your signal captured by a cell-site simulator if your phone is turned on. The best way to avoid cell-site simulators at this time is to not have a cell phone with you – obviously impractical for most of us.”

A viable option to be considered are methods of communications using end-to-end encryption.

The most notable example is Signal, a mobile app allowing to make calls and send group, text, picture, and video messages, fully encrypted. This means that the content of the communications will only be heard and read by the intended recipient. Furthermore, the app:

- Allows users to verify the identity of their contacts;

- Can encrypt the message history on the device;

- Is free and open source. This mean that its code is open for independent review and security experts can verify its protocols and cryptography.

In April 2016, the popular app WhatsApp pushed an update adding end-to-end encryption enabled by default to its chat and call functionality. To learn more about the differences between the two apps, and consider which one to try out, the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the Security in A Box project provide helpful comparative overviews and reflections.

Activists and civil and human rights defenders are among the groups that have found the adoption of these apps particularly useful to communicate and organize. For example, both Signal and WhatsApp have been reportedly used by protesters during recent demonstrations in Egypt.

However, it’s important to notice that while end-to-end encryption can help keeping the content of messages and calls private, it won’t prevent a cell-site simulator from detecting the identifying number from a mobile phone. For more information about the technology of cell-site simulators, the Street Level Surveillance Project provides a very helpful primer.

Furthermore, as outlined by the Electronic Frontier Foundation Self-Defense Guide for Activist and Protesters:

“In many countries, people are required to register their SIM cards when they purchase a mobile phone. If you take your mobile phone with you to a protest, it makes it easy for the government to figure out that you are there. […] If you absolutely must bring a mobile phone with you, try to bring one that is not registered in your name.

To protect your rights, you may want to harden your existing phone against searches. You should also consider bringing a throwaway or alternate phone to the protest that does not contain sensitive data, which you’ve never used to log in to your communications or social media accounts, and which you would not mind losing or parting with for a while. If you have a lot of sensitive or personal information on your phone, the latter might be a better option.”

Forget NSA Surveillance – Police Are Keeping Tabs On You Too. Francesca Fiorentini, AJ+.

Video documentation

Video surveillance and documentation technologies are increasingly deployed in public areas, private businesses and public institutions for monitoring purposes.

Video surveillance can be employed making use of a wide variety of technologies and tools. For example:

- Closed-circuit television (CCTV), a connected network of stationary and mobile video cameras, is an increasingly common tool to monitor a wide variety of indoor and outdoor spaces. As noted by Privacy International, “data retention laws for captured videos vary widely between CCTV operators and individual policies are seldom indicated when entering a new CCTV network”;

- Biometric technologies are often integrated in video surveillance systems, to identify individuals whose image was captured by a recording through facial recognition software;

- Concealed cameras can be embedded in clothing or placed in objects for surreptitious surveillance;

- Drones, or unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), can also be used to expand video surveillance capabilities. They can move around flexibly, are not easily visible and not very expensive. They can be equipped with very powerful lenses, IMSI catchers, radars to track locations and biometric recognition technologies for profiling purposes.

The use of video surveillance and documentation by law enforcement agencies can help identify and document incidents and crimes. But its terms of use are not always clearly regulated and their use can also become very troubling.

- Law enforcement agencies across the United States are adopting body-worn cameras for their officers. As reported by Upturn’s Police Worn Cameras: A Policy Scorecard: “One of the main selling points for these cameras is their potential to provide transparency into some police interactions, and to help protect civil rights, especially in heavily policed communities of color. But accountability is not automatic”. These cameras can make police more accountable, or simply intensify police surveillance of communities, depending on how the cameras and footage are used.

- In Brazil, biometric national identification is being implemented while still lacking accountability for the data collected, potentially providing infrastructure for a nationwide surveillance network.

- Police drones are increasingly employed to monitor protests for security purposes (to mentioned just a few examples: in Macedonia, United States, United Kingdom). Privacy activists express concern over the lack of oversight and transparency about the use of this technology, alarmed by how it could be misused by authorities to target innocent individuals.

As explained by the American Civil Liberties Union’s piece What’s wrong with public video surveillance? (providing a broad overview, valid to reflect also on democratic societies outside of the United States context), video surveillance documentation can be susceptible to different types of abuse. Among them:

- Abuse for personal purposes, when members of law enforcement agencies take advantage of the professional tools at their disposal for personal reasons (e.g. privilege, monitor, stalk, threaten individuals);

- Criminal abuse, when members of law enforcement agencies exploit their access to video documentation to pursue illicit objectives;

- Institutional abuse, when an entire law enforcement agency is turned toward abusive ends;

- Discriminatory targeting, when existing prejudices and biases influence the work of who operates the video camera systems in use.

Video surveillance technologies are evolving very quickly, and protocols to control their use and prevent abuses are not always in place as needed. Law enforcement bodies can abuse of their access to this type of equipment, hiding behind corrupted systems or taking advantage of procedural loopholes. And as an immediate consequence of this context, some of the most vulnerable targets of this misconduct are individuals and communities who are already disadvantaged, and subjected to unequal treatment and abuse of power.

Still, video documentation does not play exclusively to the advantage of who holds the power. It can also be produced and managed by who is harmed to show their reality and let it speak through the footage.

The video4change project provides an overview of the most relevant approaches that can be historically identified as examples of video technology employed to challenge a dominant power structure (part 1, part 2). They are:

- Guerrilla video;

- Participatory and community video;

- Social documentary video;

- Video advocacy;

- Communication for development and communication for change;

- Citizen journalism video and witnessing video.

Video as Evidence: A WITNESS guide for citizens, activists, and lawyers. WITNESS

Witnessing video is particularly critical when it comes to holding accountable law enforcement agencies and members who might act abusively or discriminately against marginalized groups. Affordable recording devices, often built into mobile phones, provide citizens all around the world the means to document protests, incidents and abuses. But to be able to help and protect its user, a video evidence tool needs to provide provable authenticity of its footage and ensure that the metadata embedded in the video cannot be used by third parties who might get hold of the device with harmful intentions.

It’s in this context that WITNESS, a nonprofit organization that has worked on video and human rights advocacy for over 20 years, and The Guardian Project, a research and development effort focusing on mobile security, partnered to develop a new app: CameraV.

The V stands for verification. CameraV does two things: it describes the who, what, when, where, why and how of images and video; and it establishes a chain of custody that could be pointed to in a court of law.

In the words of Harlo Holmes (The Guardian Project):

“The app captures a lot of metadata at the time of the image is shot including, not only geo-location information (which has always been standard), but corroborating data such as visible wifi networks, cell tower IDs and bluetooth signals from others in the area. It has additional information such as light meter values, that can go towards corroborating a story where you might want to tell what time of the day it is.

All of that data is then cryptographically signed by a key that only your device is capable of generating, encrypted to a trusted destination of your choice and sent off over proxy to a secure repository […]. Once received, the data contained within the image can be verified via a number of fingerprinting techniques so the submitter, maintaining their anonymity if they want to, is still uniquely identifiable to the receiver”.

Among the groups who have been using CameraV: the International Bar Association, providing lawyers with the app to gather evidence on the field to discuss their cases in court; the Georgia Legal Services Program recommending this technology to migrant workers to document that they are getting their just pay; Colectivo Papa Reto, a group of media activists collecting evidence of police violence in Rio de Janeiro.

Rebel Geeks – A Bigger Brother. With Colectivo Papa Reto, WITNESS, The Guardian Project. Directed by Orlando de Guzman and Lorien Olive, Al Jazeera English.

Witnessing video provides great opportunities to hold accountable those in power, reclaim violated rights and support restorative justice. But while being a tool of remarkable potential, it doesn’t come without risks and difficulties, for both who shots the footage and who handles it once it’s released.

As discussed by Dia Kayyali in Want to Record The Cops? Know Your Rights, even when ”it has been established that individuals have the right to record the police, what happens on the street frequently does not match the law.” Before communicating with and filming law enforcement representatives it’s always essential to be aware of your rights as citizen or visitor of the state or country where the interaction is taking place.

And once video evidence of abuse is published, what are the challenges faced by those in the position to decide how to share it safely and ethically (anyone from newsrooms, crisis responders and human rights investigators to citizens)? Codes of ethics instruct to do no harm, but how to apply this principle when working with video documentation that has been produced by others? To help fill this gap, WITNESS recently published the first version of the Ethical Guidelines for using Eyewitness Videos in Human Rights Reporting and Advocacy, examining risks involved in sharing videos of abuse, as well as ways to minimize those risks.

In conclusion

Law enforcement agencies are increasingly dedicating resources to surveillance technologies. They are institutions very closely tied to political and financial interests, which means that they are likely to act with positive intentions and less-honorable objectives in equal measure. Also, being one of the dominant groups of our societies, it’s very unlikely that any kind of updated protocol or policy will ever stop them from trying to find new gaps in the system to pursue their goals beyond what is legitimate.

What is critical to understand is that technology is not something to be fearful of altogether, as a field of knowledge largely (ab)used to aggravate control on already targeted communities.

Technology is a vast and ever-growing field, that can take very different shapes and meanings depending of who is using their knowledge to build new tools.

The need today is for more technology projects to strive to support the liberation from century-old societal systems of unrightful control and oppression.

More secure technologies need to be developed with the needs of overpoliced and underprotected communities at their core.

Outreach, educational opportunities and resources need to be dedicated to provide members of the communities who are hurt by abusive systems with the means, if they desire to do so, to become the creators of new technology aiming to fight the injustice they are oppressed by.

Secure technologies developed with the needs of unequally policed users at their core can:

- Enable targeted groups to reclaim their individual and collective right to privacy;

- Equip overmonitored citizens with tools to exercise their freedom of expression;

- Provide those fighting against abuses with evidence of corruption and wrongdoing.

In conclusion, a nod of acknowledgement to the most critical element to make tools of resistance work which is not technology in itself.

Even the most secure and inequality-aware technologies are not what makes change happen: their users – citizens reclaiming justice, activists, lawyers, journalists and rights defenders – are the ones who will truly make change a reality.