by Maya Ganesh, Dirk Slater and Beatrice Martini.

“You are welcome anytime, you’re not like others who come with their own bag of potatoes”

It’s with these words that the chair of Women’s Network for Unity (WNU), a sex worker collective based in Phnom Penh, thanked Maya Ganesh and Dirk Slater from Tactical Technology Collective for approaching the work with them with no assumptions or preconceived agenda, but eager to listen and develop their collaboration together.

Mutual trust and respect, real commitment to collaboration and flexibility are all essential elements to be responsibly equipped to work with a marginalised community. And they are not even enough. That’s why, together with Maya and Dirk, we decided to write about the experience as potato-less tech capacity builders, as we think it could greatly help other practitioners planning to collaborate with groups struggling to get their rights honoured and their voices heard.

Introduction

This article is a set of reflections and learnings from a two year project that Tactical Technology Collective (hereinafter referred to as Tactical Tech) conducted from 2010 to 2012 with Women’s Network for Unity. The project was a significant step in implementing and learning from ground-up evidence-based advocacy. In terms of capacity building of a marginalised community to use data in an advocacy context, we saw:

- a significant shift in the partners’ advocacy strategies from reactive to proactive methodologies;

- improvement in their human rights documentation processes, now including evidence gathering, data analysis and how to work with visualisations;

- development of skills applied to the effective collection and use of data for advocacy;

- new skills in analysing data resulting in a clearer understanding of the threats faced by the community;

- increased awareness about the importance of effective information management in digital documentation;development of integrated self-evaluation tools;

- deeper connection of the partners with the needs of the communities support and the variety of stakeholders they want to engage;

- contribution to the scholarship on violence against sex-workers and advocacy for their human rights.

Dirk and Maya implemented the project with support from the rest of the Tactical Tech team. I met them after completion of the project, found it could represent a compelling case study, and was invited to join them to bring an outside perspective on writing about it and present its outcomes to a wider audience, so that others working on similar projects might benefit. The post was collaboratively written and draws on Tactical Tech’s reports and notes compiled through the course of the project. We aim to provide helpful guidance to anyone aiming to work with a marginalised community to build its capacity to use data and information technologies for advocacy.

The article is structured in three parts:

- Why we did it – presenting background and context, including a definition of marginalisation, Tactical Tech’s objectives for the project and background on WNU and sex worker issues in Cambodia.

- What we did – providing details about the steps taken to implement the project, assessing WNU’s use of technology, learning about their advocacy strategies and building their capacity to use data and data visualisations in those strategies.

- What we learned – sharing reflections on the project design, notes on responsible and strategic use of data about marginalised communities and a summary of what we actually accomplished.

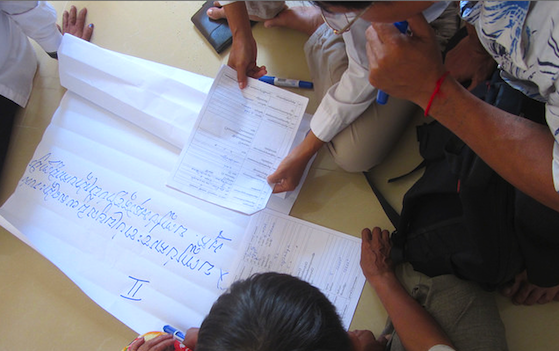

The WNU Outreach Team at work with print outs of the spreadsheets containing the data collected from their survey efforts. Picture by Dirk Slater (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

The WNU Outreach Team at work with print outs of the spreadsheets containing the data collected from their survey efforts. Picture by Dirk Slater (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

Why we did it

Tactical Tech’s initial goal was to learn how use of technology can impact and improve the advocacy efforts of marginalised communities. In this section, we’ll explain what do we mean by marginalisation, tell more about the project and give some background on WNU and Cambodia’s anti-trafficking law.

What do we mean by marginalisation

To understand what we mean by marginalisation, let’s start from a hard fact: in the eyes of the society we live in, our identities are the result of the combination of multiple categories we’re labeled with (classifying our gender, race, class, ability, sexual orientation, religion and more). Their intersections are what ranks us more or less highly, privilege-wise – possibly also ranking us so unfavourably that we find ourselves in a marginalised position. For example, two individuals with the same educational background and living in the same neighbourhood, will not be interacted with equally by society if their gender identity, race, religion (one, some or all of these) are different. Intersections matter, indeed.

Marginalisation is what happens when someone is separated – or actively excluded – from the rest of society. Marginalised individuals are often regarded as an underclass: society doesn’t provide them with equal access to basic material needs, work opportunities, education, welfare or health care. Violence and injustice experienced by marginalised communities are often invisible: their experiences and needs are ignored or forgotten by the public. When their stories are not recorded nor shared, and in absence of a framework designed to report and act on the infringement of their rights, systemic threats to their rights and safety remain unchallenged.

Caught between the tiger and the crocodile: a film by Asia Pacific Network of Sex Workers (APNSW) showing the human rights abuses experienced by sex workers in Cambodia. APNSW is a coalition of sex worker groups and projects working on issues of HIV and human rights for female, male and transgender sex workers across Asia and the Pacific.

About the project

Using Technology to Document Violations: Enabling Sex-Worker Communities to Document Violence Against Them in India and Cambodia was a project carried out by Tactical Tech in partnership with two sex worker collectives, Durbar Mahila Samanwaya Committee (DMSC) in Calcutta, India, Women’s Network for Unity (WNU) in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, and a Delhi-based research organisation, r e a c h Social Solutions (r e a c h), that studied the project from an evaluation perspective. The project was funded by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC).

Tactical Tech’s original proposal to IDRC was to improve the digital documentation techniques being employed by sex worker collectives in reporting on violence against them. An initial preparatory grant for this project (entitled Getting Sex Worker Voices Heard) explored options for enhancing sex worker advocacy through the use of technology. During this grant Tactical Tech explored a variety of options, including mapping and use of mobile devices, but the assessments revealed that neither organisation’s advocacy efforts would have been enhanced by the use of digital documentation technologies. Instead, efforts were needed to increase skills and techniques in handling information itself.

As Tactical Tech learned more about the organisations’ challenges related to their advocacy, their use of technology and the state of their existing documentation activities, and as a result of a process that was responsive and adaptive to the needs of the partner organisations, it became evident that the goals of the project needed to be re-evaluated. It was in this phase that IDRC demonstrated to be a greatly flexible and responsive funder: IDRC were fundamentally interested in the project to achieve a meaningful advocacy impact, and when Tactical Tech suggested that the project shouldn’t be technology led, they trusted their decision and kept supporting the project.

So, from an initial objective of enhancing the groups’ use of technology to document violence, the goal of the project shifted to strengthening their use of information in advocacy, and helping them refine their advocacy strategies on violence against sex-workers.

Over a two-and-a-half-year collaboration, the project achieved remarkable outcomes, such as the improvement of the partners’ human rights documentation processes; the contribution to the scholarship on violence against sex workers and advocacy for their human rights; a significant shift in the partners’ advocacy strategies from reactive to proactive methodologies, with the potential to have a beneficial impact on the lives and wellbeing of 70,000 sex workers.

About Women’s Network for Unity and Cambodia’s Anti-Trafficking Law

To provide a more detailed context to the project – and its consequent learnings – we’ll focus on the work done with one of the two partner organisations, the Cambodian Women’s Network for Unity (WNU). If interested in the work realised with the Durbar Mahila Samanwaya Committee (DMSC), please read more about here.

The toughest challenges the Cambodian sex workers community faces are caused by the consequences of the country’s anti-trafficking law – which even before being passed had a highly contested and contentious development.

The law had been enacted by the Cambodian government under pressure from the United States, which during George W. Bush’s administration handled non humanitarian and non trade related aid contingently with a number of factors such as the recipient country’s record on trafficking and an ‘anti-prostitution pledge’. From 2003, Cambodia was being given low ratings on the US’ Trafficking in Persons (TIP) Report – but the data informing such rating hadn’t been collected in the most accurate fashion. They had often been estimated on the basis of mostly anecdotal reports and frequently resulted from the conflation between sex work and trafficking – two very different things, inadequately connected on the basis of ideology and morality, rather than reality.

Not only the anti-trafficking law currently applied in Cambodia doesn’t distinguish correctly victims of trafficking by sex workers, but it criminalizes all individuals it targets indiscriminately, also exposing them to abuse of power by the police force. Advocates for sex workers in the country understand that in order to change the law, they need to change public perception, showing how the law fails to achieve its ends, as well as the harm that it does in society. This requires the careful selection of indicators that will be easy to gather, measurable, inexpensive, easy to understand, and easy to visualize.

Women’s Network for Unity is a grassroots representative collective of 6,000 sex workers in Phnom Penh and regional provinces outside the capital. The network seeks to promote the rights of sex workers to earn a living in a safe environment, free from exploitation and social stigma.

At the time of our project, WNU’s objective was to collect evidence to highlight the negative impact of the anti-trafficking law on sex-workers and to show how the police were misusing the powers this law gives them for detention and arrest.

First of all, WNU wanted to demonstrate that sex work is work. Differently from what the anti trafficking law assumed, not all sex workers have been trafficked against their will. In numerous cases, sex workers are individuals who, facing extreme financial constraints, decide to start working for the sex market, in order to maintain a basic living and support their own families. The sex trafficking myth deprives sex workers of agency and identity, andultimately prevent them from being entitled to the rights granted to other categories of citizens and workers.

In addition to the issue around misrepresentation of sex work, WNU wanted to document the illicit abuse of power committed by the police force against the workers, and its consequences on the health and finances of both the arrested individuals and, consequently, their families. Furthermore, raids and arrests under the anti-trafficking law had forced sex workers to go underground, and it became extremely difficult to reach out to them with condoms, HIV prevention, care and treatment.

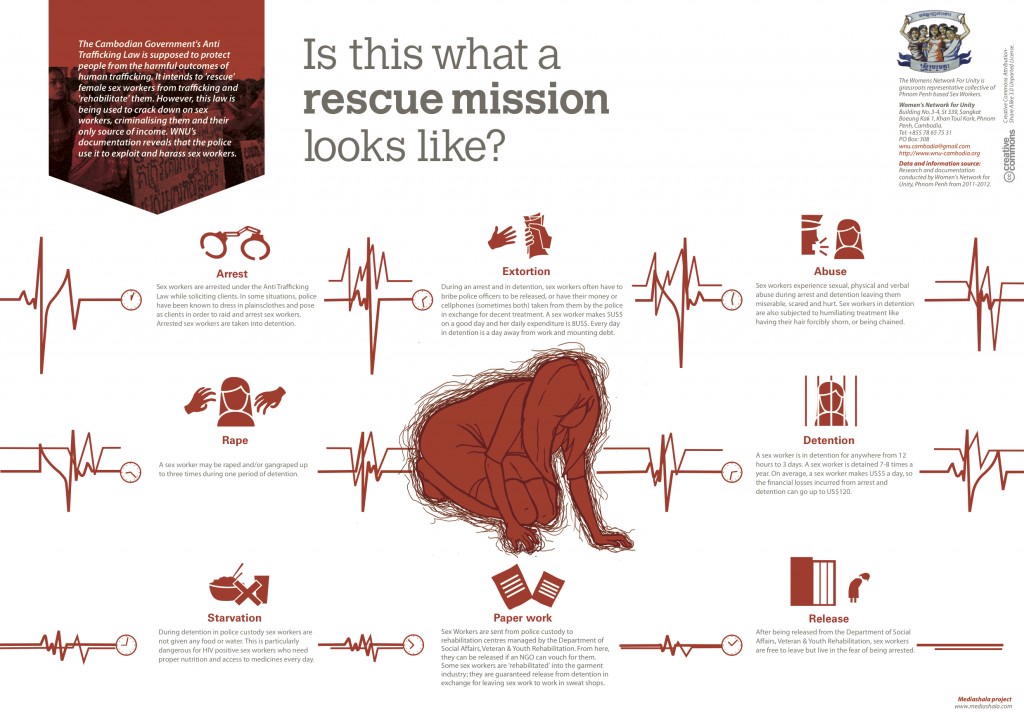

Specifically, WNU had decided to document police violence against sex workers during arrests and detention to show how the anti-trafficking law was being misused. Over the previous year WNU had already collected more than 800 detailed accounts of what happened during arrests and detention. However, upon close analysis, they realised that the information they were collecting were in fact more like case studies rather than investigations to build a serious evidence base to show how the law was being abused. For example, the anti-trafficking law states that someone detained under it cannot be held for more than a certain number of hours, after which they need to be moved through the social affairs ministry’s procedures and be released to an organisation that vouches for the sex worker’s ‘rehabilitation’. However, WNU had not documented when a sex worker was arrested and how much later she was released, so it wasn’t possible to show how long she had been in detention. In some cases arrested sex workers were being held without food and water, those who were HIV positive were denied access to their medication.Rescue Us From the Rescuers – Women’s Network for Unity (WNU).

Rescue us from the rescuers – Women’s Network for Unity (WNU).

Rescue us from the rescuers – Women’s Network for Unity (WNU).

What we did

In this section we provide details about the steps taken to implement the project, assessing WNU’s use of technology, learning about their advocacy strategies and building their capacity to use data and data visualisations in those strategies.

- Tactical Tech reviewed existing research on sex workers and developed the idea of the Atlas of Sex Work

Reviews of existing research on sex workers showed a focus on HIV prevention, care and support, and a struggle between competing lobbies who are either for or against the implementation of anti trafficking legislation as a means to end sex-work. Furthermore, data and evidence about sex worker communities were often collected by outsiders and the ownership of the data is rarely with sex workers themselves.

In order to challenge this dynamic, Tactical Tech developed the idea of the Atlas of Sex Work, a series of visualisations of the evidence to engage different target audiences for the data, using the data collected by WNU and DMSC themselves. Inspired by the Subjective Atlas of Palestine, theAtlas of Sex Work was an opportunity to showcase ideas for creative aggregations of information about the lives of sex workers and the conditions of mistreatment that they face. The concept proved useful for further developing ideas and inspiring advocacy messages for target audiences.

- We started the work with WNU with assessing the organisation’s abilities to conduct documentation of violence against sex workers.

We asked WNU to walk us through their current documentation process and show us their outputs. We also examined their current use of technology and realised that their paper based systems worked best and that the only improvement to be made was to have them put the information in spreadsheets.

- We asked the organisation to explain their advocacy strategies.

Talking about it together, we realised that the most effective way to frame their work towards the achievement of a tangible impact was to ask whether and how the documentation and reporting of violations against sex workers could improve their ability to conduct advocacy and decrease the amount of violence happening in the sex worker community.

Removing the emphasis on digital technologies and focusing on the use of data in strengthening their advocacy techniques was an important step. This flexibility was critical in moving forward and it was important for us to clarify this internally, with partners and the funder.

- We provided them with a self-reflective research methodology that allowed them to evaluate their progress with advocacy.

Working closely with Veronica Magar and Rituu Nanda from r e a c h, WNU developed a self-reflection tool to conduct their own assessments. We were interested in documenting how the process of using data, and shaping advocacy goals and statements affected how WNU were able to think about their advocacy and the use of data. The team felt that the self-assessment tool and exercises provided were of great value. They recognised the need to expand their advocacy approaches beyond the confrontational approach they formerly relied on and to acquire relationship-building skills to engage in cooperative advocacy approaches.

- We organised workshops for WNU on how to develop survey tools and questionnaires along with the use of video and audio for interviewing.

The first workshop, led by the Cambodian Centre for Human Rights (CCHR) and attended by WNU’s outreach team members (primarily sex workers), focused oncreating survey tools for data collection. Two survey tools were created for data collection to support the advocacy campaigns on Stop Raid and Rescue and Sex Work is Work. After implementing the survey tools for six months, WNU realised they needed to better support their advocacy aims. The second workshop focused on training WNU to conduct interviews using audio and video. Each workshop gave WNU skills that had previously only been deployed by actors from external organisations who were ultimately in control of the outputs.

These two workshops gave WNU the skills to gather their own data and use it for their own purposes without the interference of external agendas. Evidence of WNU’s commitment to their own capacity-building and development can be read into their decision to revise the questionnaires they developed with CCHR’s assistance, and conduct a second round of data collection as they felt the first questionnaire was not really addressing their advocacy objectives. By the end of the project, the WNU staff members had tangibly strengthened their confidence on their ability to manage different aspects of the data collection, management and analysis.

The WNU Team at work. Picture by Dirk Slater (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

- We conducted a workshop focusing on how to analyse their own data, and understanding the basics of statistical analysis.

As the main responsibilities of the majority of WNU’s staff members were not dependent on being computer literate, their in-house tech capacity was quite low. However, the members of the team working on the project with us were interested in acquiring new technology skills, and our partnership gave them an opportunity to do so.

- We focused on a pragmatic use of technology, rather than combat erratic connectivity or aim to create uniform levels of computer literacy.

WNU greatly benefitted from transferring their data from paper to spreadsheets. An immediate challenge for them was the use of non-standardised Khmer fonts on their computers, which led to problems with transferring their data to other programmes. Luckily this issue was identified early on and promptly rectified. WNU also used Excel’s built-in functionality to produce graphs and pie charts that were used to make some preliminary visualisations. In particular, this allowed them to produce leaflets highlighting the increased violence against sex workers through the implementation of the anti trafficking law, which they adopted to illustrate the problem during meetings with government officials.

Data and evidence about sex worker communities are often collected by outsiders and the ownership of the data is rarely with sex workers themselves. As a result of doing the evidence collection themselves, WNU acquired a clearer picture of who perpetrates violence and were able to connect the violence directly to policy. This inspired a significant shift from reactive advocacy strategies to proactive ones, and had the effect of both enabling WNU to have a stronger connection to their own communities and building their own confidence in their ability to create an accurate picture of what is happening in their communities.

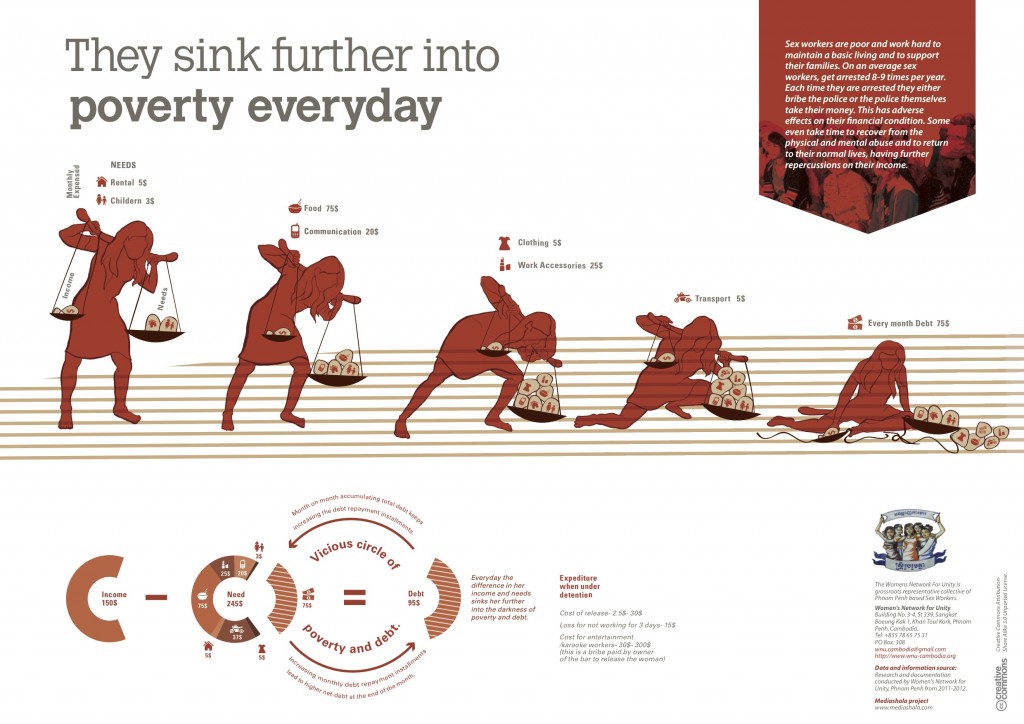

WNU also developed key skills in analysing and understanding their own data. They now have a clearer understanding of how the anti trafficking law creates more violence but also how the acts of raid and rescue actually drive sex workers deeper into poverty.

- We helped WNU develop a design brief for their visualisations, as part of the Atlas of Sex Work framework

We showed the group examples of visualisations of data, particularly infographics that had been used in advocacy, and asked them to find and share local examples of infographics. By doing this the group was able to break down existing graphics into trying to come up with a process for how they were developed, how the data was sourced and visualised, to figure out the actual process of how information can be leveraged in different way to create advocacy messages.

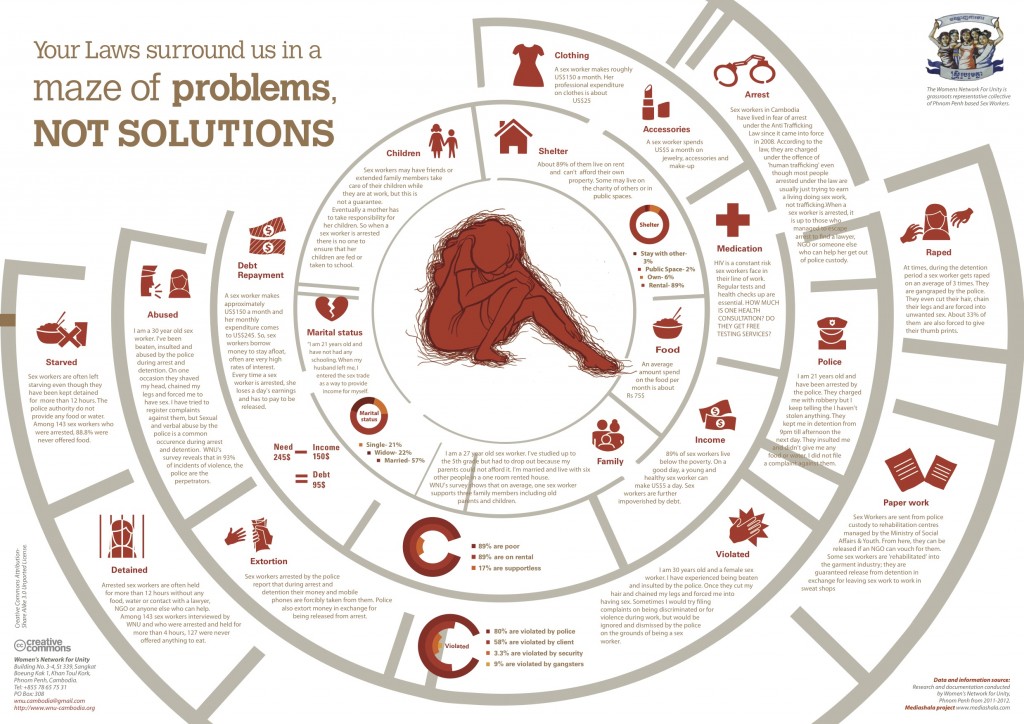

We then asked them how they would present their data to various stakeholders and worked together to develop three briefs for visualisations of their evidence: Rescue Us From the Rescuers, Your Law Brings Us More Problems, Not Solutions and Not Being Rescued from Poverty. These have been then developed into visual advocacy materials by the design research firm Mediashala.

- In parallel, using pilot data, WNU made their own maps and charts about the impacts of the anti-trafficking law on sex workers and shared them with policymakers and partner NGOs.

WNU report that the aggregation of evidence about violence against sex-workers, even in a pilot form, garnered interest and attention from their peers and audiences and gave the small collective a great deal of confidence and assurance about working with evidence and how it can strengthen their advocacy. They are also being approached by other organisations and institutions interested in using their data to support other advocacy efforts around gender-based violence.

Your Law Brings Us More Problems, Not Solutions – Women’s Network for Unity (WNU).

Your Law Brings Us More Problems, Not Solutions – Women’s Network for Unity (WNU).

What we learned

In this section we highlight our most relevant learnings focusing on three core aspects of the project:

- stakeholders engagement, trust and capacity building

- project design and choices about technology and processes

- responsible and strategic use of data about marginalised communities

We also present what we consider to be our core achievements in conducting the project.

Stakeholders engagement, trust and capacity building

- When introducing yourself to the community you’ll work with, be clear about your role and goals. You are not a funder nor a technology provider. You are working with the community to help improve its advocacy power.

- Support the existing advocacy aims and goals of the community and leave assumptions about what they should be at the door. Marginalised communities can be highly suspicious of the intentions of international NGO’s coming to work with them, and this is largely because they have been taken advantage of.

- Build mutual trust and respect. Deal with delicate topics and experiences part of the community’s reality respectfully and always focusing on supporting it in accomplishing its mission.

- There are going to be sensitive topics which will need to be covered, and no level of tact will ever be too much: be prepared, ask advice to professionals who already talk about delicate issues with members of the community you’re working with, be aware of cultural customs, always be respectful, never judgemental.

During most of our project with WNU, we managed to avoid conversations about titillating details regarding the sex workers’ experiences. But for the sake of data, when brainstorming about how to visualise the economics of sex work, we found ourselves in need to ask for the price of the services they provided. We motivated our need to ask in detail (and crossed fingers hoping not to damage our until then fruitful working relationship with this request), and luckily our question was welcomed with a laughter (!). For the record, the services are not priced by the sexual act, but by a combination of other factors, such as duration of the encounter and economic class the client belongs to.

- It’s important to have longevity in relationships with not just the organisations working on the project but with the individuals at those organisations as well. This is not just about building trust, but about working with individuals who understand the project and how it has progressed.

- Communication is key. Regular and consistent communication is an essential element of remote management, and face-to-face site visits are extremely productive and critical to move the project along (especially when cultural and linguistic differences come into play). It’s also important to have patience and understand when other priorities need to be heeded.

- Make sure that the data collected are shared with the members of the community you work with. This is extremely important in raising awarenessand furthering conversations about the community’s rights.

- Working with a marginalised community means that emergencies and moments of crisis can and will happen, and will likely influence the work. Therefore, support and allow substantial changes during the course of the project, using an adaptive, rather than prescriptive approach.

- The opportunity to work with a community on strengthening its advocacy power can offer the chance for institutional reinforcement. This can take the shape of training to: understand and analyse visual advocacy and the use of evidence in campaigns from around the world; map audiences and develop advocacy messages for target groups;develop formats for the visualisations/outputs with the collaboration of an information designer to communicate messages in an accessible visual format. These are all elements of a capacity building approach focusing on giving a community a new perspective on how to improve its advocacy.

Not Being Rescued from Poverty – Women’s Network for Unity (WNU).

Not Being Rescued from Poverty – Women’s Network for Unity (WNU).

Project design and choices about technology and processes

- The project should begin with a proper assessment relating to the use and application of technologies to the community’s goals.

- Sketch out the scope, scale, geographic coverage, and comprehensiveness of the data collection initiative that you are planning.

- Identify as early as possible the technology which can most effectively and sustainably help the organisations you work with achieve their goals. Groups that adopt technology platforms and devices without reviewing and stringently assessing their overall approach to working with information, often find themselves struggling to manage their technologies instead of leveraging their information.

- Examine the appropriate role of emerging technologies with communities lacking a proper strategic foundation to them effectively.

- Don’t bring in new technology if not necessary, and incorporate processes, systems and platforms that will enable, support and help process their information needs in a way that has a strong impact on the community’s core objectives.

- But also: support grassroots communities to leverage social media technologies to convey their messages. Digitally-enabled activism has become a strong factor in global politics but many smaller groups are being left out primarily due to infrastructural limitations (from poor bandwidth to lack of multi-language platforms). Basic digital advocacy trainings can be useful for grassroots communities in leveraging their information more effectively.

- Design implementation projects that integrate self-reflection tools. Active, participatory reflection on process can be very useful if it is integrated with the project activities and simultaneously develops strong monitoring and evaluation methodologies and feedback loops.

- Participatory action and research can greatly help the community think more strategically, and with a better analysis of their own context.

- Produce draft visualisations of the data that the organisations collect early as this can lead to a turning point in the way that the organisations understand how data can be used in advocacy.To be done as early as possible in the project to start showing how powerful it can be.

- Focus on replicability. Identify aspects of the intervention that may have relevance for the community you work with in the future, as well as for other similar marginalised communities.

Responsible and strategic use of data about marginalised communities

- Data and evidence about marginalised communities are often collected by outsiders and the ownership of the data is rarely with the communities themselves. Therefore, support the community you work with in understanding how to aggregate different kinds of data as evidence about their issues, and how this may be visually represented, and equip it to take on further advocacy projects and develop its own materials in the future.

- Data collection efforts are extremely beneficial to the community, not just in terms of their own projects and work, but in building confidence and skills. Always put the community at the centre of the data collection process as well as the discussions and decision-making around what the data would be used for.

- Focus on the risk of unsafe exposure, the tension between damaging visibility and participation. It’s essential that activists working with marginalised communities are fully aware of this aspect and how to responsibly deal with it, making sure not to harm the vulnerable individuals involved.

- Identify what the best means are for working with data and evidence from an action and advocacy perspective – as opposed to a more academic approach, fairly common in NGOs, which translates the data collected in detailed theoretical research, which can be helpful for documentation purposes but does not help towards the most tangible action-focused needs of grassroots communities.

- Community-based groups could be supported to use different kinds of open data that do exist in order to develop their advocacy materials. If more public data was open, more grassroots groups could learn to make use of it to contextualise their advocacy, and open data platforms could be useful for advocacy across the social justice spectrum.

- There needs to be a greater connection between open-data movements and grassroots advocates to ensure accessibility and usability of data released by public institutions. The kinds of knowledge created by grassroots groups also needs to find greater connection with the kinds of knowledge developed by more well-resourced and powerful groups such as research institutes. Essentially, an open data approach to community owned and community based data could be extremely beneficial to advocates.

What we achieved

The project was a significant step in implementing and learning from ground-up evidence-based advocacy. In terms of capacity building of a marginalised community to use data in an advocacy context, we saw:

- a significant shift in the partners’ advocacy strategies from reactive to proactive methodologies;

- improvement in their human rights documentation processes, now including evidence gathering, data analysis and how to work with visualisations;

- development of skills applied to the effective collection and use of data for advocacy;

- new skills in analysing data resulting in a clearer understanding of the threats faced by the community;

- increased awareness about the importance of effective information management in digital documentation;

- development of integrated self-evaluation tools;

- deeper connection of the partners with the needs of the communities support and the variety of stakeholders they want to engage;

- contribution to the scholarship on violence against sex-workers and advocacy for their human rights.

In conclusion

The opportunity to work with and for a marginalised community is an exceptional chance to impact many people’s lives profoundly thought the collaborative identification and creation of technology solutions which can equip them to achieve their goals. Capacity building and strategic advocacy can help their experiences become visible, injustice evidenced and called out, their rights reclaimed.

In conclusion, summing up the most fundamental advice emerging from our case study, we recommend to:

- listen to and learn from the community, keeping assumptions at bay;

- give ownership of the work to the community itself;

- build capacity tailored to its needs and abilities, accessibly and sustainably;

- provide it with the tools and methodologies which will equip it to work independently on more successful initiatives in the months and years ahead.

We hope this write-up will be helpful to others working on similar projects and we’ll be glad to hear your thoughts and feedback on it in the comments below.

This article is published here in its full version and was also posted by Tactical Tech (edited version) and Dirk Slater (full version) on their respective sites.